No excuse for boring you, my loyal readers, with this, but here goes:

A. Trying to keep up the momentum, I’m switching back and forth between 3-4 writing projects. When I get stuck on one, just switch. Don’t even think about, just keep writing, with the goal still being 2 novels and 2 collections of short stories ready to go (to an editor, most likely) by end of June. And that science book. Anyway, what’s in the hopper:

Layman’s Guide to Understanding Science: Right around 10,000 words, on temporary hold. The comments, especially from Dr. Kurland and some of the commentators here, made me think – always dangerous. The question is not so much what science IS – which can be approached, I think, from several valid angles – but rather, in what sense should a layman care what science is. It will do little good to be technical accurate if my imagined reader doesn’t see any point to it. Ya know? So, I’m letting that one stew for now.

Working title “It Will Work” the first 6,000 or so words of which appeared on this blog as a series of flash fiction posts. (CH 1 CH 2 CH 3 CH 4 CH 5 CH 6 CH 7) I couldn’t seem to stop writing this, right up until I could, and it got the second most positive comments of anything I’ve written here, (1) so it seemed primed to become a short novel. It was one of the three novels-in-development in the Novels folder I set up back in January. At about 8,000 words at the moment.

Always told myself I needed to settle on an ending, so I knew where I was going with this – even though the 7 fragments were each tossed off totally seat-of-the-pants. Well, just today I started outlining what the kids these days might call the Boss Battle, the final test of Our Hero – and, it rocks so hard. Want to talk stupid? I was getting choked up telling my wife about it. I wrote it long before the current insanity, but, given the current insanity, it all makes so much more sense. As far as a “things done got blowed up good” by bombardment from space and aliens in power armor scene set on a distant moon of a far-away planet can be said to relate to current events. (answer: quite a bit, really.) Anyway: got the finale & denouement outlined, and am in the middle of the middle section. My only fear, if you can call it that – if I keep the pacing such as it has been so far, I’ll wrap it up in +/-30K words. Don’t want to stretch it simply for the sake of stretching it, but do want at least 40K words – Pulp Era novel length. Not a real problem until it is….

The White-Handled Blade – the Arthurian YA novel set in modern day Wales, the first 25% of which is the novella several generous readers here beta read for me a couple years ago. Currently sits at about 13K words. This one is exciting, but I want to do more reading in Arthurian legends and outline a longer path, as in, a potential series, before maybe writing myself into a corner. The story as it stands now is little more than a free retelling of the Lynette & Lyonesse story as told by Malory, ending right before Gareth makes his untoward advances toward Lyonesse. So, obviously, I would continue along those line BUT I want to introduce more stuff that will let me go in any number of Arthurian directions. I already have several of the important knight (reimagined as middle-aged academics, because I find that amusing), so, in future works, it will be easy to take some side-trips to Scotland or the Orkneys or Cornwall or France. I want to keep Lynnette as the heroine, because I like her, and she was designed from the ground up as someone the reader could relate to: she’s fiercely devoted to her older sister, loves but has trouble communicating with her dad, gets snubbed and bullied at school, can hold a grudge, but never gives up and is as brave as needed to rise to the occasion. And is otherwise a blank slate, so there’s nothing in the way to seeing yourself in her shoes.

So I’m rereading Malory and reading the Mabinogion for ideas. The farther back in time one goes, the crazier the legends become, such that getting a glimpse into Malory’s world – 15th century retelling of much older stories -is a lot easier than getting into the world of the Mabinogion, which are thought to be older still. Even Malory requires a bit of gymnastics to get into the moral mindset of people who seem to kill each other rather gleefully at the drop of a biggin, but not like the Welsh tales. And then there’s the French version…

Speaking of writing something I didn’t set out to write and would have never imagined writing, it seems YA fiction is mostly characterized as follows:

- no sex

- no swearing

- not too much gore

Which, frankly is a pretty fair description of anything I’m likely to write. On the other hand, Hunger Games is about children killing each other for the amusement of the powerful – I’d take a lot of sex and swearing before I’d consider that entertainment…

Anyway, it seems to be common industry knowledge that YA readership includes large numbers of adults who are just sick and tired of all the gratuitous sex and swearing and violence in mainstream stuff. So, from that point of view, pretty much anything (well, except this) I write would qualify, but I have never consciously tried to write YA. I’m putting in plenty of what I hope to be interesting non-childish philosophical and political and moral stuff. So – huh? Anyway, I’ll have to be careful of how I market this stuff. Studying up on that in parallel. Hope to get back to it soon, but it’s It Will Work is on the front burner at the moment.

Longship, the working title of the Novel That Shall Not Be Named (wait! doh!), some sections of which I’ve thrown up here on the blog, is the one that has both been percolating in my mind for a decade or two AND the one I’m having the least success in hammering into a actual novel or 4. On the back burner.

Finally, Black Friday is another bit of flash fiction fluff (well, 1400 words, so not exactly flash fiction…) that seemed ripe to expand, so I’ve been outlining that one, too. Have put in some work on it, but not in the form of adding to the wordcount.

B. This brings me to another consideration: The science and education stuff (remember that education stuff? I seem to have forgotten) I will publish under my own name. However, if I’m hoping to actually make a little money off the SF&F stuff, it would seem prudent to market under a nom de plum. I’m under no illusions that I’m anybody important, but underestimating the pettiness of our self-appoint betters is a fool’s game.

On a related note, I’ve taken a few baby steps towards hardening my superversive presence online, including a Brave/Duckduckgo browsing combo, a protonmail account and staying off Google as much as I can. I want to go :

- secure VPN

- secure website hosting

Just want off, as much as possible, the Bidenriech’s surveillance network. A know I guy…

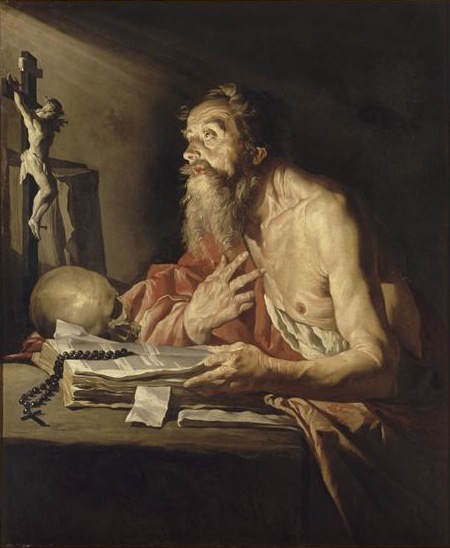

C. The 16 year old Caboose just mentioned that his favorite books include a book on spiritual teachings from the perspective of a demon, a book on politics from the perspective of rabbits, and a post apocalyptical novel about a monastery.

Kids these days. I asked him what about that book about the short dude with hairy feet trying to return some stolen jewelry? He laughed.

D. Slept 8+ hours straight last night, the first time that’s happened in months. Felt very good. Been getting 4 -6 hours most nights since the Crazy Years became manifest – wake up, can’t go back to sleep, get us and try to do something. I could get used to that.

E. Got a few hundred more bricks. The neighbors who I, being a solid California suburbanite, hardly know, have twice now over the last few years of the Great Front Yard Brick Insanity and Orchard Hoedown, have, unbidden, offered me bricks, because I’m the guy with the brickwork. So, dude around the corner had this pile of bricks he wanted gone – 6 1/2 wheelbarrows full. Maybe a short block away.

One Load 3, I think it was, I came off the curb a little too hard and bent the metal wheel supports (it’s a cheap and old wheelbarrow) such that the wheel now rubbed against the underbelly of the tub section. I was able to brut-force them straight enough so that I could limp that load home.

So, had to repair the wheelbarrow. Two bolts that hold the handle arms to the tub section, which I had replaced a few years back with a couple far too long bolts I had lying around, had worked themselves very loose then rusted into their new loose positions. This made the load likely to shift from side to side as you rolled – no biggie with a load of dirt, dangerous and tiring with a load of bricks. But the bolts were carriage bolts, so there was no easy way to grip the head from the top. After a applying a bit of WD-40, tried to grip the excess bolt with plyers while using a crescent wrench to tighten them up. The first nut moved a little before the plyers had shredded the threads on the bolt and would no longer prevent it from turning; the second budged not a whit. Jury-rigged the ugliest solution: took some heavy wire, bent it unto a U shape, then crimped it onto the bolts between the nut and the tub – one on the side I’d gotten a little tighter, and two one the side I’d been unable to move.

And – it kinda works. Reality often fails to suitably rebuke me for my stupid ideas, thereby encouraging me to keep coming up with more of them. It’s going to get me killed someday…

Next, for the bent arms: Cut a scrap of walnut into two maybe 8″ pieces, placed them behind the bent arms, clamped them until the arms were more or less straight and in contack with the wood, then drilled some wholes and put in some tiny screws to hold it all together.

And – that worked, too. Now have a much more stiff structure and a couple inches of clearance between the tub and wheel. See what I mean? If these slapdash ideas keep working, I’m going to keep doing them.

Next step: replace the 16+ year old cheap and falling apart wheelbarrow. Once some stupid repair idea fails to work, that is.

F. Got the front yard orchard cleaned up, pruned, fertilized, mulched, copper-sprayed, and watered, not in that order. So, that’s done for now. Next, finish the brickwork, paint the house, get it fumigated for termites, replace the dying major appliances, put in this year’s vegetable garden, marry off a son on the East Coast in May, and goodness knows what else. And teach a couple history classes. Shaping up to be a busy Year 63 for me. And write two novels, put together two books of short stories, and write a book on science – in my spare time.

Yes, I am freaking INSANE.

- Most positive comments: One Day. Heck, even Mike Flynn liked it enough to comment – I’m still blushing.