Thanks to people (Sarah Hoyt in particular – thanks, Sarah!) linking to the last 2 posts, many more people are taking a good hard look at the history of education in America, the number one project of this blog. So let’s go back to the beginning. Long time readers have seen this all before; new readers might find it helpful. It’s a bit long, but I think worth it.

Why is education in America such a mess today? Another canard that need dispelling: everything was fine, back in the (pick an era) 50s! Back then, docile and obedient students got great educations in public schools (and their Catholic Mini-Me’s) all across America! It’s only since the 60s and all those damn hippies that things went bad, and only in the last decade or two that schools became miserable indoctrination camps! As discussed very briefly here, that’s wishful thinking – compulsory public schooling has never been ‘good’ in any sense a rational parent would consider good. This failure of the schools to teach what a loving, rational parent would want for his child is no accident.

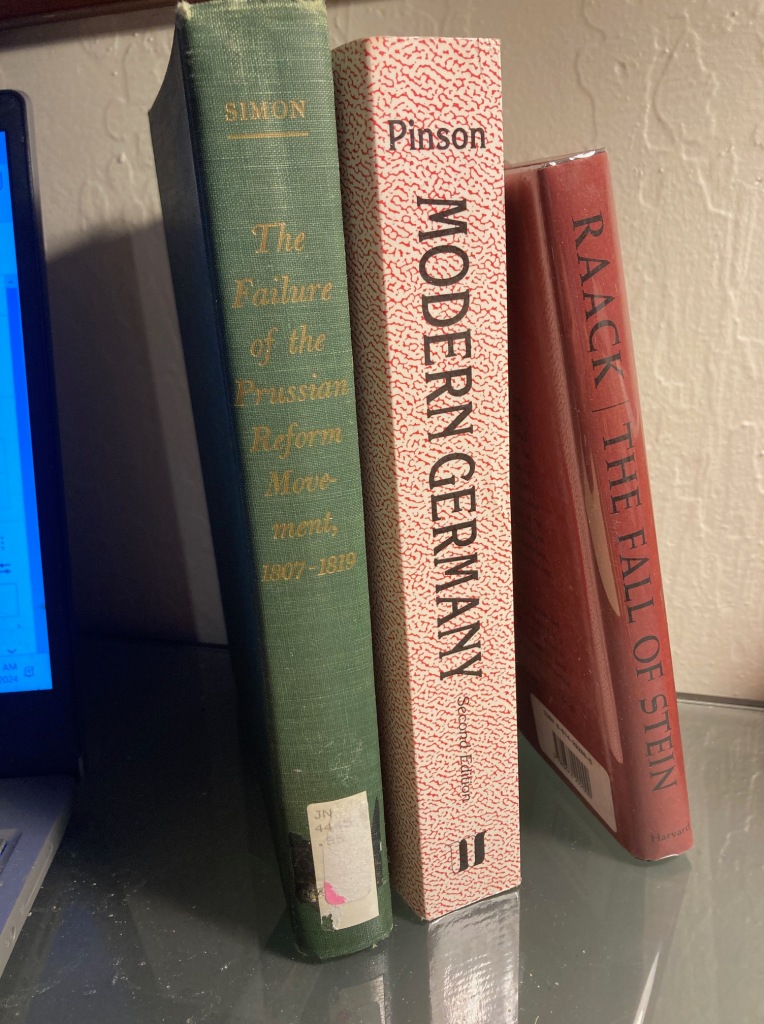

It is well known among homeschoolers, unschoolers, and other double-plus ungood wrongthinkers that American schooling is based on the Prussian Model, often referred to as Factory Schooling. While calling it Factory Schooling is largely true, we misunderstand the stated and demonstrated goals of this system if we think obedient factory workers are the main goal

Here’s what happened: In 1806, Napoleon’s army conquered the Prussians; the Kaiser and his family were forced to flee to Russia. Prussians, who saw themselves as the quintessential Germans, were humiliated. Sitting on the seats of power in Berlin were despised Frenchmen, who were dictating Enlightened (after the fashion of Napoleon) laws and basically rubbing Prussian noses in it.

Along comes one of the leading Prussian intellectuals of the day – Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose philosophizing bridges the teaching of Kant and Hegel. He’s a German Romantic, which, as the Oracle Wikipedia puts it, “were hostile to political liberalism, rationalism, neoclassicism, and cosmopolitanism.” So Fichte, and his German Romantic contemporaries, reject liberalism, which here includes the idea of individual human rights; rationalism, meaning making logical sense is not a priority (see: Hegel’s Logic for a complete exposition); neoclassicism, meaning don’t look to the past masters for guidance; and cosmopolitanism, meaning don’t think of yourself primarily as a citizen of the world, but rather (in his case) as a German.

Fichte is alarmingly nationalistic, saying Germans are the purest, most lofty thinkers on the planet, and must lead the lesser peoples into the next stage of human development.

So Fichte deliver a series of lectures over the winter of 1807-1808 called Addresses to the German Nation. These lectures were presented to the kind of people who would pay to hear a lecture by a philosopher in the dead of winter in Berlin – I don’t know what to make of that. Down the street were the occupying French soldiers and politicians.

Why this is important: The year after these lectures were delivered, the Prussian Minister of Education, von Humboldt, established a new thing on earth – the Prussian research university. Rejecting neoclassicism like a good German Romantic must, these new universities were dedicated to Progress, to moving the world (via Germans, of course) forward. Rather than being devoted to passing on a culture and cultivating a liberal (free) mind, these universities – and all American state and almost all private universities have adopted these principles – are dedicated to improving the world. Such improvement is to be defined and enforced by top men, such as Fichte and von Humboldt.

Since Education Departments had yet to be invented, von Humboldt put Fichte in charge of the Philosophy department at the newly-founded University of Berlin. In this role, Fichte and his followers got to shape and gatekeep the Progress in education described below. Over the next 50 years, many American sons went to Prussia to study and get a (newly created) PhD from these research universities. These men then became the leaders and gatekeepers at all the newly-founded state Education Departments, the Normal Schools for training teachers, and eventually, all the major colleges and universities. Fichte’s ideas thus became the basis of American compulsory age-segregated graded classroom education to this day. (Note that the insane idea of segregating children by age and grading them like lumber or eggs is yet another product of the Prussian research universities – imported into the US in 1848. No one anywhere did school like that before.)

After many pages dedicated to praising real Germans and insulting people (the French, say) who speak the language of their conquerors, he finally gets to the point: Germans have long been miseducated, and, in order to take the great and glorious place in History, they have to do a better job going forward. I’ll let the man speak for himself:

Fichte believes the state has the right and duty to simply remove all children from their families and communities until they have raised to manhood:

“It is essential that from the very beginning the pupil should be continuously and completely under the influence of this education, and should be separated altogether from the community, and kept from all contact with it.”

and:

”Education should aim at destroying free will so that after pupils are thus schooled they will be incapable throughout the rest of their lives of thinking or acting otherwise than as their school masters would have wished.”

Of course, it is not to be expected that all parents will be willing to be separated from their children, and to hand them over to this new education, a notion of which it will be difficult to convey to them. From past experience we must reckon that everyone who still believes he is able to support his children at home will set himself against public education, and especially against a public education that separates so strictly and lasts so long.

“that separates so strictly and lasts so long” – we’re talking handing over your kids to the state at some young age and not seeing them again for many years. I could see how moms and dads might have a problem with this.

To put it more briefly. According to our supposition, those who need protection are deprived of the guardianship of their parents and relatives, whose place has been taken by masters. If they are not to become absolute slaves, they must be released from guardianship, and the first step in this direction is to educate them to manhood. German love of fatherland has lost its place; it shall get another, a wider and deeper one; there in peace and obscurity it shall establish itself and harden itself like steel, and at the right moment break forth in youthful strength and restore to the State its lost independence. Now, in regard to this restoration foreigners, and also those among us who have petty and narrow minds and despairing hearts, need not be alarmed; one can console them with the assurance that not one of them will live to see it, and that the age which will live to see it will think otherwise than they.

9th Address, pp 127.

See how that works? Petty, narrow-minded people with despairing hearts will be alarmed at having the state seize and physically remove their children from them for duration of their education, for the purpose of training them to restore the state to its proper independence. Such people – us! – are to be consoled with the assurance that none of us will live to see the state restored to its glory. We may miss our children, but we won’t have to endure the glorious future.

Now, assuming that the pupil is to remain until education is finished, reading and writing can be of no use in the purely national education, so long as this education continues. But it can, indeed, be very harmful; because, as it has hitherto so often done, it may easily lead the pupil astray from direct perception to mere signs, and from attention, which knows that it grasps nothing if it does not grasp it now and here, to distraction, which consoles itself by writing things down and wants to learn some day from paper what it will probably never learn, and, in general, to the dreaming which so often accompanies dealings with the letters of the alphabet. Not until the very end of education, and as its last gift for the journey, should these arts be imparted and the pupil led by analysis of the language, of which he has been completely master for a long time, to discover and use the letters. After the rest of the training he has already acquired, this would be play.

Fichte, 9th Address, pp 136

To sum up: a kid is to spend, effectively, 24 x 7 X 365 in school for around 10 years, learning to be a good German, how to really focus on the task at hand (2) but doesn’t learn reading and writing (and, one assumes, arithmetic) until something like age 15 or 16. If you can read and write, you don’t have to pay attention to the teacher as much – you can take notes, and review later. This will not do, as the child is to accept the state trained and certified teacher in the place of his displaced father, and fulfill his need for approval and love by pleasing that teacher. The magical education works, according to Fichte’s understanding of Pestalozzi, by having the student utterly emotionally dependent on pleasing the teacher, doing what the teacher wants him to do in the way the teacher wants it done, always eager for approval. There is no fallback: by design, a child who fails to please his teacher has no recourse, not to family, not even to books. His family has abandoned him, as far as he knows, and he’s not allowed to explore the world through reading, where he might come across other ways in which people interact.

In modern Europe education actually originated, not with the State, but with that power from which States, too, for the most part obtained their power—from the heavenly spiritual kingdom of the Church. The Church considered itself not so much a part of the earthly community as a colony from heaven quite foreign to the earthly community and sent out to enrol citizens for that foreign State, wherever it could take root. [note: ‘foreign’ is about as strong a put-down as Fichte uses, the opposite of German, his highest praise.] Its education aimed at nothing else but that men should not be damned in the other world but saved. The Reformation merely united this ecclesiastical power, which otherwise continued to regard itself as before, to the temporal power, with which formerly it had very often been actually in conflict. [note: Luther sought to have the state seize monasteries and turn them into state schools; much of his correspondence was with secular leaders urging them to pursue various programs. Eventually, we reached the point today where German churches are state-supported institutions.] In that connection, this was the only difference that resulted from that event; there also remained, therefore, the old view of educational matters. … The sole public education, that of the people, however, was simply education for salvation in heaven; the essential feature was a little Christianity and reading, with writing if it could be managed—all for the sake of Christianity. All other development of man was left to the blind and casual influence of the society in which they grew up, and to actual life. Even the institutions for scholarly education were intended mainly for the training of ecclesiastics. Theology was the important faculty; the others were merely supplementary to it, and usually received only its leavings.

Address 11, pp 164

Finally, is there any role for the Church? (He’s talking Lutheran, or at least. Protestant, churches here. That the Catholic Church might have a role was of course beyond consideration.) Not really:

Now, if for the future, and from this very hour, we are to be able to hope better things in this matter from the State, it will have to exchange what seems to have been up to the present its fundamental conception of the aim of education for an entirely different one. It must see that it was quite right before to refuse to be anxious about the eternal salvation of its citizens, because no special training is required for such salvation, and that a nursery for heaven, like the Church, whose power has at last been handed over to the State, should not be permitted, for it only obstructs all good education, and must be dispensed with. On the other hand, the State must see that education for life on earth is very greatly needed; from such a thorough education, training for heaven follows as an easy supplement. The more enlightened the State thought it was before, the more firmly it seems to have believed that it could attain its true aim merely by means of coercive institutions, and without any religion and morality in its citizens, who might do as they liked in regard to such matters. May it have learnt this at least from recent experiences—that it cannot do so, and that it has got into its present condition just because of the want of religion and morality!ibid, pp 166

There’s a lot going on in this paragraph:

- Fichte asserts that the Church has at last surrendered its power to the State, and that this is a good thing;

- The state has an entirely different aim for education than the Church

- The state should not ‘permit’ the Church, which should be ‘dispensed with’

- The state is concerned with education for life on earth. Earlier, Fichte described how this whole afterlife business interferes with men doing what men – German men, of course – need to do to bring about heaven on earth, that we obtain immortality through making the nation stronger and better, and need to embrace the goals of the nation (German, of course) and focus on that

- The state has previously ignored religion and morality in education, but now must take it up. Earlier, he argues that state education IS simply education in religion and morality, that reading and academics can and should be delayed until the end of the educational period, if indulged in at all. The important thing is to teach children to love the fatherland and do what they are told by their masters.

- “Recent experiences” include having their armies crushed and lands overrun by the loathsome French, who, even as Fichte was delivering these talks, were sitting in the seats of power just blocks away.

There’s a dreadful amount more to this. Just know that, at the roots of our system of schooling are the following core beliefs:

- Parents are the problem schools are designed to solve.

- The state has the duty and power to determine and deliver education. Parents, and most certainly students, have no say in how our kids are educated.

- All of the student’s time should be taken up by schooling as much as possible (The state may have found it impractical to simply seize our kids, but they do their best to keep them under constant control.)

- Formal religion is to be replaced by the state; education is to be shifted from the idea of learning to do right so as to gain Heaven to learning to do what you are told in order to achieve Heaven on earth – as defined by your betters

- The three R’s don’t figure into it, and, in fact, are dangerous temptations to thinking for yourself. Only after you have become thoroughly obedient to the state can such extras like reading, writing, and math be taught to you.

- People, especially us commoners, are Blank Slates for all practical purposes.

I could give examples of how each of these beliefs are manifested in modern schooling, but, as this is getting really long, I leave that as an exercise for the reader.